I work in the cheese department of a busy, upscale grocery store. We sell around $3,000 worth of cheese a day. If you figure the average price of cheese is about $5 a piece, that means we sell 600 pieces of cheese a day. I personally cut, wrap, price, and label about a quarter of that. That means I wrap about 150 pieces of cheese a day. Multiply that by the four days a week I work and you get the figure of 600 pieces a week.

I can do this work with my eyes closed. I can cut, slice, and wrap cheese with the precision of a machine. While I work, it’s possible for me to hold long conversations with actual people, or if no one else is around, the people in my mind. Customers come in with their cheese problems, questions, and complaints. Sometimes I can help them.

“Can I help you find a cheese?” I say.

“I’m having friends over tonight and I want this certain cheese but I don’t remember the name,” the woman replies.

“Can you describe it?”

“Well, let me think … it was Italian and was kind of like a Parmesan but fruitier.”

“Was it the Piave Vecchio?”

“Yes! That was it.”

And I feel good. But often I can’t help customers—we don’t have what they’re looking for. Or, as is often the case, they don’t really know what they want. Something sharp and spreadable? (It doesn’t exist.) Something to use in place of a Cheddar in macaroni and cheese, but that has flavor—but not too much flavor? I sigh and try to be helpful. But sometimes I can only point them in the general direction of a good melter (Fontina, Gruyere) or something their in-laws from Michigan will like (Cotswold?). They leave, not dissatisfied necessarily, but confused, almost melancholy.

My job wears on me, but it’s not dealing with customers that’s hard, it’s the fact that I have to stand in one place for eight hours a day twisting my arms and bending down to pick up wheels of cheese over and over until I have shooting back pain and tingling in my extremities. One summer my arms started going numb. More specifically, the ring and pinkie finger on my right hand. Sometimes, especially if I’d been on my bike for any length of time, my entire hand and arm would completely lose feeling. It’d take hours for it to come back and sometimes the persistent tingling would never completely go away.

I started to feel like my job was killing me. My back hurt all the time, and now, to make matters worse, I couldn’t feel my fingers. One of the cheese managers at another store had recently come down with an extremely rare bacterial infection in his spine. It ate away some of his vertebrae, he could barely walk, and he’d almost died. The doctors told him that it was very rare, there were only a couple known cases worldwide, and they had no idea how he’d gotten it. But one thing that all these cases had in common was that everyone who’d been infected had worked with dairy. All of us cheese workers whispered under our breath that it must’ve been the cheese.

Another one of our managers was allergic to the sanitizer we used for our cheese-cutting equipment. She had to continually apply an anti-inflammatory cream to her hands. The backs of them were covered by flakes and scabs.

Yet another manager went to the doctor and found that his cho lesterol was so high that he would have to be put on medication if he didn’t change his diet. Still another manager, who was fond of saying that “you can eat as much cheese as you like as long as you eat fruit,” found out he had diverticulitis.

As is often the case with me, I started complaining about my numb hands to anyone who would listen. Finally, a friend of my parents told me to stop complaining and go to the doctor. He was right. It could be something serious. My sister Sarah told me it was probably the beginning of carpal tunnel syndrome. She’d got it from bartending and had had similar symptoms. The woman who worked at the coffee shop across the street from my house told me she’d had carpal tunnel and had to have surgery. “It was very simple,” she said, knocking the basket out of the espresso machine with one deft move of her wrist. “Snip snip, and I was cured.” My mother was convinced my back was going out.

I went to the doctor and found out that it was nothing. I told my grandfather about it and he told me that he’d had the same symptoms for a year before they went away. And my numb fingers did eventually heal themselves.

Now, years later, I deal with a strange electro-shock sensation that runs down my right arm every time I move a piece of cheese from the scale to the cart we use for stocking. My knees crack every time I squat down. My lower back aches. But if this job didn’t create such strange disturbances in the body, any respite from them wouldn’t be so appreciated. I savor these breaks from pain in whatever form they appear to me. I squat behind the cheese case to clean a knife in the bucket of sanitizer. My knees crack on the way down and I feel the stretch along my calves and hamstrings. The feeling is beautiful and quiet. I pause here, my body frozen, half-crouched down where no one can see me. I let myself rest for 30 seconds until I hear a voice wafting over the case.

“Can I talk to someone who knows something about cheese?”

Bagel

It’s 8:00 a.m. A man walks up to me in the cheese section and these are the first words I hear this morning: “If I were a bagel and I didn’t want anyone to find me, where would I be?”

I stop what I’m doing and look up. “Well, if you were a bagel and you didn’t want anyone to find you, you wouldn’t be in the bakery, but that’s where you are.”

The man just looks at me confused.

“The bagels are in the bakery,” I say.

He frowns and walks away.

Fontina

“I found a fly in my cheese,” the woman says, handing me a bag across the counter. “I just thought you should know.”

Sure enough, there it is, half-encased in a wedge of Italian Fontina. It must’ve flown into the still-hardening cheese and drowned there. Well, there are worse ways to die than drowning in cheese. “Do you want your money back?” I say.

The woman frowns and shakes her head. “I just thought you should know,” she says.

It bothers me when customers do this. Just take the money. “It’s not a big deal,” I say. “Are you sure you don’t want your money back?”

“I just thought you should know there was a fly in your cheese.” She crosses her arms.

I look down at the bag of cheese. So now it’s MY cheese. That’s the way it always works. I feel like telling the woman that I don’t make cheese, I just cut it and wrap it, and even if I did there’d be nothing I could do to prevent this little guy from flying into my warehouse, landing in my cheese, and dying. And even if I were to call up the distributor and ask where they buy the cheese, and then I were to call the Italian cheese-makers and complain about the flies, they’d just shrug and tell me “Tough Titty.” Or something like that. I don’t speak Italian.

Entry Level Goat Cheese

“I’m looking for an entry level goat cheese,” the man says to me. He has some flour tortillas and a couple of chicken breasts in his shopping cart. He looks worried.

I wonder what an “entry level goat cheese” is. I know what a goat is. I know what cheese is. Goat cheese is the result of a process. It’s what happens when grass interacts with a goat, its hormones, a farmer, mold, and time. It’s what happens when a bodily fluid is ex posed to extremes in temperature, to centuries-old traditions and the market economy. Goat cheese is the result of an accident eons ago when early herding cultures started milking their goats and left some of the milk in a leather sack overnight, hanging from the eave of their hut, or in the corner of their cave. Goat cheese is what hap pens when you age the goat’s milk, then wrap it in wax, in leaves, or esophageal tubing. I know what this is.

But what is entry level? The point at which you enter? Where the grass enters mouths, stomachs, udders? Is it where the milk enters the world, hot and steaming from the teat? Is it where I enter the grocery store, enter my employee number into the time clock and don my hat, nametag, and apron? Is the entry level where the wire enters the cheese, splitting it in two? Is it where the cheese enters the plastic wrap, and gets entered into the scale at $15.99 a pound? Is entry level the place where I spend eight hours a day cutting, wrapping, weighing, and pricing the byproduct of an animal? The result of a process that begins and ends with digestion, that begins with the earth and ends with the earth? Is it where I package my own bodily fluids, my blood, sweat, and tears into eight-hour shifts, ten-minute breaks, and two-week pay periods?

I look at the man, his face impatient, eager to suckle at the teat of my vast cheese knowledge. I feel like telling him that every entry level is also an exit level. That all hierarchy is an illusion. That he should follow his heart. Instead I recommend the Goat Gouda, the Goat Jack, or if he’s in the mood for something saltier, the Murcia Curado.

My Vast Cheese Knowledge

1. My favorite grocery store joke goes like this. A man walks up to the register and unloads his basket. He slaps down some Hungry Man TV dinners, single serving ice cream tubs, a toilet paper four-pack, a single serving of macaroni salad, and one apple. The cashier looks at his groceries and says, “You must be single.”

The man looks up and says, “Can you tell because of what I’m buying?”

“No. I can tell because you’re ugly.”

2. We sell the most string cheese on Sunday nights.

3. Because of their longer commutes, suburbanites have less free time. They’re also more likely to have expensive nail jobs that they don’t want ruined by crumbling up Gorgonzola. The store will charge them on average about a dollar extra per pound to pour Gor gonzola from a five-pound bag into small tubs so that they don’t have to touch the cheese, so that all they have to do is open the plastic container and pour it into their salad bowls, dress the salads, toss, and consume. A dollar per pound so that besides the cow’s in testinal and mammary parts, not to mention the liberal amount of microorganisms in the blue cheese mold, the only things that will touch their Gorgonzola will be made of steel and plastic.

The company we buy the crumbled Gorgonzola from charges us about 50 cents extra a pound. Sounds like a bum deal until you remember that the cows work for free.

4. I am working in the cheese department with my back to the counter. I hear a man and a woman talking about cheese at the cheese case.

“Do you want to get a Camembert?” the man asks.

“No.”

“How about some Oregon Blue?”

“You know what I like?” she says. “I like the Gorgonzola that is already crumbled.”

Silence.

The woman speaks again. “By the look on your face I can tell that you think that’s not very good.”

“It’s just that what I like isn’t the same as what you like. It’s not better or worse, it’s just taste.”

From this I can tell that the two of them haven’t been dating very long.

5. A man walks up to the cheese case and says, “I was in Spain a month ago and I had this really good cheese called Queso. Do you have it?”

6. A woman walks up to the case and says, “I was in France a year ago and we had this really good cheese called Fromage. Do you have it?”

7. Women say, “I can’t find the cream cheese.”

Men say, “If I were looking for the cream cheese, where would I find it?”

8. Three men walk up to the counter. One of them points to the Flora Nell blue cheese and says, “Look! That cheese is named after me!” He looks up at me. “Is this good?”

“The Flora Nell? Yes, it is good.”

“Oh. Flora Nell. I thought it was Flora Neil. You should have said Flora Neil. You could’ve gotten a sale.”

“I thought your name was Nell,” I say.

“I am looking for an Italian cheese,” says one of the other men. “It was creamy—”

“Fontina?” I ask.

“No.”

“Was it a brie?”

“No.”

“Taleggio?”

“Yes! Fellatio!”

“Taleggio?” I say again.

9. I am trying to sell goat cheese with Oregon hazelnuts and Frangelico. I offer two women small samples. Their eyes close and their heads tip back slightly. “Oh my God! It’s like cheese ice cream! Where can I find it?”

I show them where it’s located in the case. Both of them pick it up and put it in their baskets.

A man walks up and is browsing the cheese case.

“Do you want to try something fabulous while you’re browsing?” I ask. The man nods and I hand him a sample of the Frangelico cheese.

He puts the sample in his mouth as I describe the cheese to him. His face suddenly turns sour. “It’s sweet,” he says, as if I’ve just given him a sample of his own semen. He spits the cheese into his palm and walks away in disgust.

11. I offer the old woman with the mustache a sample of the French triple cream Delice de Bourgogne.

“I love this creamy cheese,” she says. “Hard cheese really stops up my bowels.”

I don’t think I’ve heard her right. “I’m sorry. Hard cheese what?”

The woman licks the taster spoon and smiles at me. “IT STOPS UP MY BOWELS!”

“Oh,” I say. “Interesting.”

“After World War Two,” she continues, “I went out and bought a huge block of Tillamook cheese. During the war we couldn’t buy that stuff without stamps. Anyway I ate the whole thing. I’ve never been the same since.”

Two hours later an old man walks up to the case and I give him a sample of the Cabot Clothbound Cheddar. “That is so good,” he says.

“Isn’t that amazing?” I say.

I give him a sample of Shaft’s Bleu Vein.

“This is so tempting,” he says as he puts the cheese in his mouth. “But I shouldn’t be eating cheese.”

“Why not?” I ask. Why do I always ask?

“Because it makes my skin break out right here.” The man points to the space between his very bushy eyebrows.

Two women approach the cheese case with two children. They taste some eight-month Manchego from the counter and I offer them some Delice de Bourgogne. The older woman loves it. “This is so good!” she says. “Where is this in the case?”

I point it out for her.

“Boy, that is good cheese. How much salt is in that cheese?”

“I don’t know,” I say. “Probably a lot. You know, your best bet is Swiss cheese or a reduced sodium cheese.”

“I’m a diabetic and on chemo,” the woman says. “I’m not supposed to have a lot of salt. Those reduced salt cheeses are usually pretty awful.”

“I know,” I say.

Book Club Cheese

A couple years ago, when my mother first started attending a book club, she asked me to pick out some cheeses and give a little talk on them when it was her turn to host the meeting. The ladies were impressed, or at least they acted as if they were. Several years later, my aunt (who is in the same book club) called in a panic from Trader Joe’s wanting to know what I would recommend now that it was her turn to host. Over a spotty cell phone connection, I coached her through the Trader Joe’s cheese section. I talked her into a Manchego. She acted as though I’d just helped her perform brain surgery. “Martha!” she said. “You’re a lifesaver!”

A couple months later I’m cutting cheese while a woman brows es the case. She starts grunting and throws the brie down in disgust. “Do you have Delice de Bourgogne?”

“No, but we have this one. It’s very similar,” I say, pointing out another triple cream.

The woman ignores me and starts scanning the case as if she’s looking for the wire to cut to a ticking time bomb. “It’s my book club tonight!” she says. “You guys don’t have any of the cheeses I need!” She picks up a Camembert only to drop it half-heartedly. It rolls on top of the Red Dragon.

“Well, if you’d like to taste anything, let me know,” I say cheerfully.

She ignores my offer and frowns. “Is this good?” She holds up a cave-aged Gruyere.

“It’s great.”

The woman places it in her basket.

“What book are you discussing tonight?” I ask.

She doesn’t look up. “Angel Fire.”

“Hmm, never heard of it.” I continue wrapping cheese.

The woman is rifling through the Scottish cheddars and I realize this is probably not the best thing to say. She groans again in frustration, throws a piece of cheese down, and walks away in a huff.

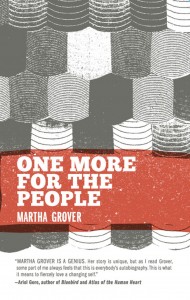

Later that day I go home thinking about the stress surrounding book clubs, how women are often more interested in impressing each other with their hosting abilities then they are in discussing the book. As a lover of books and writing, this irks me. But as a lover of cheese, I should be okay with it—right? And I wonder—what kept me from telling the woman at the cheese counter that I am a writer? That I am writing a book?

I have spent over half my life serving people, starting as a dishwasher when I was fifteen. In the past fifteen years I’ve been a busser, a hostess, a waitress, a cocktail server, a deli worker, a prep cook, and now a cheese clerk. Rule number one of the service industry is the same thing they tell nurses in nursing school: don’t talk about yourself to the patient. In other words, people are coming to you to ask your expert opinion about cheese or their blood pressure or whatever—they’re not coming to you to get to know you as a three-dimensional human being. They don’t care who you are.

Until I worked with a certain woman at a busy Italian restaurant in my early twenties, I’d always taken it for granted that everyone knew this rule. She was my own age but had never worked in a restaurant before. She’d just graduated from college with a degree in English and dance.

One night after work, she and I went out for a drink to commiserate. “I’m running around pouring people water,” she said, “and clearing their plates and everything, and it’s like—they don’t know anything about me. They don’t know I’m really a dancer.”

I stared at her for a minute and took another sip of beer. “You don’t want them to know that,” I said.

“But they look at me and think I’m just a hostess. That that’s all I am.”

“Honey,” I said, feeling for the first time like a veteran of the service industry, “that knowledge is what’s yours to keep. That’s your treasure. Keeping that private is the only way you’re going to keep from going crazy.” And it’s true: if you can’t deal with this, you might not last long serving people. In the customer service world, in the world of giving the most of yourself away on a daily basis, there’s this paradox where in the end, you really give people the least. You become a cut-out of yourself. You have neither great loves nor great hates. You are not a hater of Cotswold—you are just not a “fan” of Cotswold. You do not confess that you would give your left arm for a vacation in France, you only say that your customer’s week in the wine country sounds “fantastic.”

And so, I wonder, in the case of the book club cheese, with my own book finally coming out, will I break my own rule and tell customers that I am really a writer? That this cheese gig is only my day job? That they should care more about the book than the cheese? Or maybe I should be taking advantage of the fact that people care so much about cheese? I mull this over all day. As I label the Oscar Wilde Aged Irish Cheddar, his musing face stares out at me. “Look what they do,” he whispers. “You die in a gutter and they put your face on a piece of cheese.”

When I get home from work I ask my boyfriend if he thinks people would pay to have an in-home tasting and seminar on cheese. “Taught by me,” I say hopefully.

“I don’t think so, honey,” he says.